Introduction

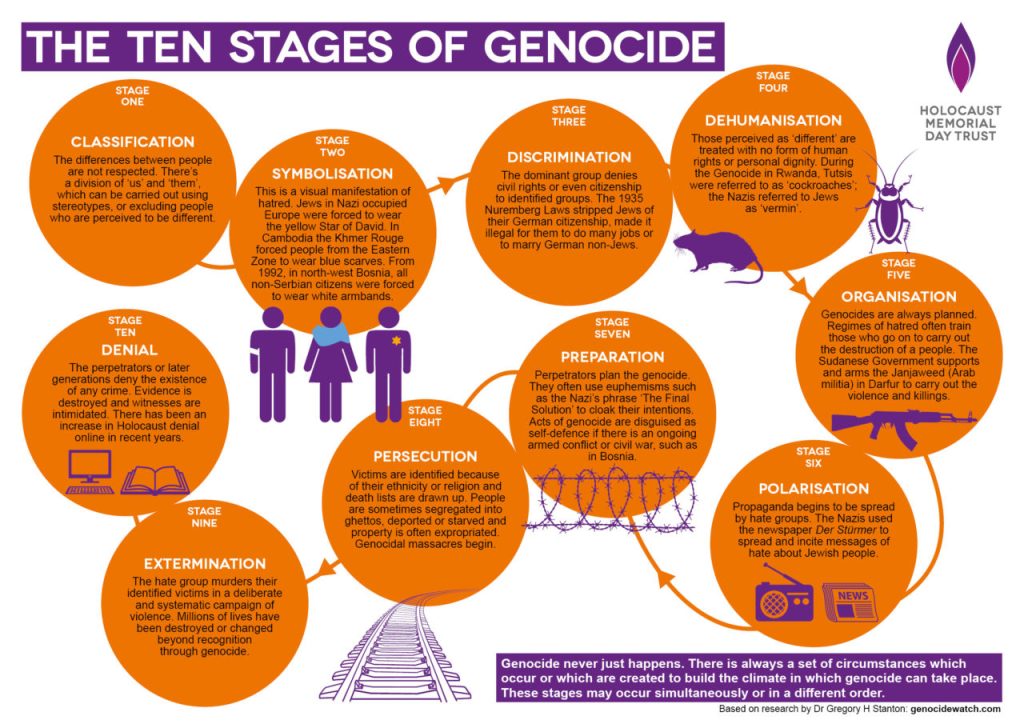

South Africa’s sociopolitical landscape is scrutinized here through the lens of the ten stages of genocide (as defined by Dr. Gregory Stanton): classification, symbolization, discrimination, dehumanization, organization, polarization, preparation, persecution, extermination, and denial. These stages represent a progression from early warning signs (like classification of “us vs. them” groups) to the ultimate horror of extermination and its denial by perpetrators. This report evaluates current evidence of each stage in South Africa using recent government statements, human rights reports, news coverage, and academic analyses. Key focus areas include ethnic or racial group tensions, hate speech and propaganda, the role of government or militias, and incidents of systemic violence or displacement. The goal is to determine which stages are observable in South Africa today and to gauge the risk level associated with each, given the country’s history and present dynamics.

Classification

Classification is the defining of groups into “us and them,” often by ethnicity, race, nationality, or religion. In South Africa, stark social and political classifications persist despite the formal end of apartheid in 1994. Public discourse frequently divides people along racial and national lines – for example, citizens versus foreign nationals, or black versus white communities. During the May 2024 general elections, several political candidates openly scapegoated foreign African nationals, painting migrants as a source of problems and thus reinforcing a divisive “us vs. them” narrative. Independent UN human rights experts have likewise condemned the rising “us versus outsiders” rhetoric targeting migrants, refugees, and asylum-seekers in South Africa. This rhetoric explicitly classifies African foreign nationals as separate from and inferior to South African citizens, marking a clear instance of early-stage classification. Likewise, some extremist political voices classify along racial lines; for instance, elements of the opposition Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) often draw a sharp line between the black majority and the white minority, referring to whites collectively as “colonizers” or beneficiaries of “white monopoly capital”. South Africa’s own president has acknowledged that the society remains “highly polarized” along racial and class lines even decades after apartheid – an implicit recognition that classifications of groups still strongly influence social relations. In summary, the classification stage is evident in South Africa’s current sociopolitical context, as various actors continue to divide society into defined groups and blame certain groups for the country’s ills.

Symbolization

In the symbolization stage, labels or symbols are assigned to differentiate the classified groups – sometimes through derogatory names, stereotypes, or even physical markings. While South Africa today does not have official laws forcing people to wear identifying symbols as in some historical genocides, negative labels and slurs are frequently used against target groups. For example, black African immigrants are often derisively called “amakwerekwere” – a slur implying foreigners speak unintelligibly – and are portrayed in popular xenophobic narratives as criminals, job stealers, or disease carriers in local communities. Hate speech on South African social media and in street protests has included highly offensive racist slurs and even comparisons of foreign nationals to “cockroaches,” invoking language chillingly reminiscent of past genocides. A 2022 joint investigation by Global Witness and a South African legal center found numerous examples of xenophobic slogans and insults on social platforms, including calls to “kill” migrants and hashtags from campaigns like “#OperationDudula,” which were approved for publication despite containing dehumanizing content. Political discourse also employs symbolic language: in a recent incident, a splinter party aligned with former President Zuma labeled President Cyril Ramaphosa a “house negro” for cooperating with a predominantly white party, while calling a white opposition leader his “slave master”. Such charged terms are symbols intended to stigmatize those seen as betraying their race. On the opposite end of the spectrum, white supremacist groups propagate their own symbols of hate and fear – for instance, the now-defunct Boeremag and newer fringe groups rally around old apartheid-era flags or other insignia as symbols of white identity under threat. In summary, symbolization is present in South Africa through verbal and visual epithets: while not state-imposed, societal use of derogatory labels, hate slogans, and loaded imagery serves to mark certain groups as the “other.”

Discrimination

Discrimination involves a dominant group using law, custom, and institutional power to deny rights or opportunities to target groups. In contemporary South Africa, overt legal discrimination on racial grounds (the foundation of apartheid) is outlawed – the 1996 Constitution is founded on non-racial, egalitarian principles. However, institutional and societal discrimination persists, especially against non-citizens and other marginalized groups. The United Nations special rapporteurs reported in 2022 that “discrimination against foreign nationals in South Africa has been institutionalized both in government policy and broader society”, creating barriers for migrants in accessing services, jobs, and justice. One example is Operation Dudula, an anti-immigrant vigilante campaign, whose very name means “to force out”. It began as a social media movement and evolved into coordinated township patrols that demand identity documents and evict undocumented migrants. The existence of such groups reflects and amplifies discriminatory attitudes at the community level – effectively barring foreign nationals from certain neighborhoods or economic activities (such as informal trading in townships) through intimidation. On a policy level, xenophobic sentiment has seeped into proposals and actions: authorities have periodically conducted mass identity raids in immigrant neighborhoods and businesses, ostensibly to root out illegal immigrants, but often using excessive force and sweeping up even legal asylum-seekers, as documented by human rights NGOs. In late 2023, rights groups had to take legal action after police unlawfully arrested registered asylum seekers at refugee reception offices, leading to detentions and deportations without due process, in violation of international law. Beyond migrants, discrimination concerns also arise in economic policy: affirmative action and Black Economic Empowerment laws, designed to uplift the historically oppressed black majority, have stirred grievances among some white South Africans who perceive these measures as “reverse discrimination.” While aimed at equity, these policies do sort opportunities by group identity and contribute to political polarization (for instance, far-right groups cite them as evidence of bias against whites). Furthermore, corruption and bureaucratic hurdles in immigration and asylum systems compound discrimination – bribes are often needed for foreigners to access basic documentation, effectively denying equal protection under the law. In sum, systemic discrimination is evident: especially toward African immigrants (who face institutionalized xenophobia and barriers to employment or safety), and to a lesser extent via contentious race-based policies that, while intended to rectify past injustice, are exploited by extremists to claim they are the new victims.

Dehumanization

Dehumanization is a pivotal stage where hate propaganda vilifies the target group as less than human – equating them with animals, vermin, or diseases – thereby morally excluding them from society. South Africa has witnessed alarming examples of dehumanizing speech directed at various groups. Perhaps the most pronounced is the rhetoric against foreign African nationals. Xenophobic vigilante groups and some politicians routinely describe undocumented immigrants as “parasites” or “criminals by nature”, blaming them for crime, drug trafficking, or economic woes. Social media and protest chants have explicitly compared migrants to “cockroaches” that must be exterminated, echoing language used in the Rwanda genocide. A recent investigation highlighted real-world examples of posts calling to “shoot” and “kill” foreigners, rife with slurs and incitement. These dehumanizing tropes make violence seem acceptable by implying the victims are an infestation rather than human beings. Tragically, such language has precedents in action: during a wave of xenophobic unrest in April 2022, a mob in Diepsloot went “door-to-door” hunting for undocumented migrants; one Zimbabwean man, Elvis Nyathi, was beaten and burned alive by a crowd – a horrifying act suggestive of how far dehumanization had stripped away his attackers’ empathy. Witnesses and media reported the assailants justified the murder as “getting rid of criminals,” as if the victim were not an innocent father of four but a depersonalized threat.

Dehumanizing rhetoric has also surfaced in racial contexts. Extremist elements of the EFF have flirted with genocidal language toward the white minority: EFF leader Julius Malema once ominously declared “We are not calling for the slaughtering of white people – at least for now”, insinuating that killing whites could be an option in the future. He also warned that “the white man has been too comfortable for too long,” casting an entire group as complacent oppressors who might deserve violent upheaval. Such statements stop short of outright incitement but strongly dehumanize whites as a monolithic antagonist class. Although a South African court in 2022 ruled that Malema’s infamous “Kill the Boer” chant (aimed at white farmers) was not hate speech in a legal sense – framing it as historical political expression rather than a literal call to murder – the chant’s wording undeniably dehumanizes its targets as enemies to be “killed”. The fact that this and similar songs (with refrains like “shoot to kill”) are still sung at rallies is deeply unsettling to the white farming community, many of whom feel under siege. On the other side of the racial divide, fringe white supremacist groups also engage in dehumanization, referring to black South Africans with apartheid-era slurs or claiming the country is being “ravaged by savages” in their propaganda. These narratives, while not mainstream, circulate online and reinforce reciprocal hatred.

In summary, dehumanization is strongly present in South Africa’s current climate. Hate speech and propaganda against foreign nationals is particularly rampant – with explicit calls for violence and derogatory comparisons to vermin documented on social media – and anti-minority rhetoric from certain political actors further strips target groups of their humanity. This stage significantly raises the risk of wider violence, as it primes portions of the population to tolerate or commit atrocities against those deemed sub-human.

Organization

In the organization stage, hate and violence become structured – whether by the state or extremist groups – through militias, vigilante groups, or terror cells preparing for or carrying out attacks. South Africa does not have government-sponsored death squads or clandestine militias planning genocide. However, there are organized non-state actors and networks that further the persecution of target groups. The most prominent example is Operation Dudula and its affiliates: initially a social media campaign in early 2021, Operation Dudula quickly transformed into a coordinated movement with chapters in multiple townships. Members of Dudula (often wearing identifiable clothing or uniforms during marches) systematically target migrant communities – organizing marches, roadblocks, and even house-to-house raids to root out foreigners. According to UN experts, “Operation Dudula has become an umbrella for the mobilization of violent protests, vigilante violence, arson targeting migrant-owned homes and businesses, and even the murder of foreign nationals.”. This shows a chilling level of organization behind xenophobic attacks: what might seem like “sporadic” mob violence is often incited and orchestrated by group leaders, who use social media and local cell structures to direct crowds towards migrant-rich areas. Indeed, extremist groups have made xenophobia a “central campaign strategy”, meaning political parties themselves are providing organizational backing to anti-foreigner sentiment. For example, some politicians openly campaign on promises to deport immigrants and have been seen alongside or encouraging Dudula activists.

On the racial front, the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), while a legitimate political party, at times exhibits quasi-militaristic organization in its intimidation tactics. The EFF’s supporters often don red uniforms and berets and have stormed businesses or farms under the banner of “expropriation” or anti-racism causes. Their coordinated chants and marches to songs like “Shoot the Boer” demonstrate an organized capacity to intimidate a targeted minority (white farmers), even if they stop short of physical violence in most cases. Genocide Watch specifically pointed to the EFF as an extremist faction driving polarization and urged President Ramaphosa to “denounce the Marxist, racist Economic Freedom [Fighters]” to undercut its influence. There have also been reports of paramilitary-style training or mobilization on the far-right white side: groups such as the “Boerelegioen” (Army of Boer people) have emerged, preparing for a feared racial conflict. In one recent court case, a wealthy individual tried to leave millions of dollars to the Boerelegioen to advance its cause, which included spreading racial hate and separatism; the South African court interdicted this, declaring any so-called “white genocide” to be “clearly imagined” and against public policy. The Boerelegioen case reveals that while these extremist groups exist, the state has thus far constrained their organizing efforts (in this instance, by financially crippling the group and rejecting the narrative it was founded on).

Overall, organized activity around hate and violence is present in South Africa. It is not centrally coordinated by the government, but rather manifested in vigilante groups (e.g. Operation Dudula) and political movements (EFF’s militant posturing) that provide structure and encouragement for persecution. This organized nature of hate makes the situation more dangerous – attacks are not purely random but can be instigated in multiple locations by extremist leadership. The government’s response has been mixed: while top officials condemn violence, law enforcement has largely failed to dismantle these networks or consistently hold their members accountable, allowing organization to continue with relative impunity.

Polarization

Polarization is the stage at which extremists drive wedges between groups, using propaganda and laws to deepen division, and silencing moderates who oppose hatred. By many accounts, South Africa has entered this stage. In fact, Genocide Watch currently classifies South Africa at Stage 6: Polarization, due to the severe degree of societal division and inflammatory rhetoric observed. The polarization is two-fold: there is racial polarization between blacks and whites fueled by mutual mistrust and extremist narratives, and nationalist/xenophobic polarization between South African natives and immigrant communities.

On the racial side, discourse has grown more openly hostile. Far-left groups like the EFF amplify grievances about enduring racial inequality (which is very real) into messages that border on racial incitement, as noted earlier. Simultaneously, far-right voices (including some international commentators and local white nationalist groups) amplify a counter-narrative of a supposed “white genocide” or the “end of white South Africans,” stoking fear among the white minority. These two extremes feed off each other, each painting the other group as an existential threat. The result is a shrinking middle ground for constructive dialogue on racial reconciliation. Even mainstream politics recently saw polarization play out: when the long-ruling African National Congress (ANC) was forced into a coalition with the historically white-led Democratic Alliance in 2024, some opposition figures from the EFF and a breakaway Zuma faction lambasted the coalition as “consolidating white power”. They refused to join a unity government explicitly because they deemed the DA a party of white interests. Thus, rather than celebrate a multi-racial partnership, extremists cast it as betrayal, further dividing supporters along racial lines.

With respect to xenophobia, polarization is even more palpable on the ground. Hate groups broadcast polarizing propaganda against foreigners – for instance, the slogan “Put South Africans First” has trended, insisting that immigrants (especially other Africans and Asians) are “taking” jobs, houses, and women from citizens. Community radio, WhatsApp groups, and rallies spread rumors blaming foreigners for every local crime or economic problem. This has whipped up local residents against migrant neighbors, fragmenting once-mixed communities. The UN special rapporteurs warned in 2022 that anti-migrant discourse from “senior government officials” was fanning the flames of this polarization, as even some leaders started scapegoating migrants for societal woes. During the 2024 election campaigns, multiple candidates (across party lines) leaned into such rhetoric, calling for deportations and stricter immigration as vote-winning strategies. This mainstreaming of xenophobic narrative pushed South African politics further into an “us vs. them” mindset, where moderating voices that call for tolerance or remind people of pan-African solidarity are drowned out. Notably, President Ramaphosa in his 2024 inauguration speech acknowledged the nation’s “toxic divisions” and “high polarization”, urging a return to Mandela’s ideal of unity. His plea itself highlights how polarized the environment has become that a head of state must explicitly call out and counteract it.

Polarization is also evident in the targeting of moderates. Stanton’s model notes that extremists attack and silence the voices in their own group who seek compromise. In South Africa, one can see shades of this: for instance, black South Africans who oppose xenophobia or who work with whites are sometimes derided as sell-outs. The Zuma-aligned party calling Ramaphosa a “house negro” (for partnering with whites) exemplifies an attempt to shame and silence a moderate approach. Likewise, within white communities, those who support social transformation or denounce fringe racism might get labeled traitors by hardliners. These pressures make it dangerous for bridge-builders to speak up, thus amplifying extreme positions.

In sum, polarization in South Africa is at a high level. The country exhibits exactly what Stage 6 entails: hate groups broadcasting polarizing propaganda (against immigrants and other races), political exploitation of divisions, and intimidation of moderates. This stage being well underway is a serious warning sign; Genocide Watch’s designation of an Alert at this stage underscores that urgent measures are needed to protect vulnerable groups and rebuild societal trust.

Preparation

Preparation is the phase when plans are made for genocide: the perpetrators identify their intended victims, stockpile weapons, train militias, or legislate emergency powers to enable mass atrocities. In assessing South Africa, there is currently no clear, open evidence of a coordinated “genocide preparation” effort by the government or major mainstream actors. Unlike historical cases (where death lists were drawn up or ghettos established at this stage), South Africa’s state institutions are not preparing any action to physically annihilate a group. On the contrary, the government has frameworks (at least on paper) to combat racism and xenophobia – such as the National Action Plan launched in 2019 to address intolerance. The South African military and police are not arming for a civil war along racial lines, and there are no known concentration camps or genocidal legislation being set up.

That said, vigilance is warranted. The ingredients for potential mass violence do exist, even if an explicit plan does not. Certain extremist groups appear to be in a preparatory mindset, if not capability. For example, far-right Afrikaner survivalist groups have long hoarded weapons and drawn up “contingency plans” for civil collapse – essentially preparing for what they believe will be a racial doomsday scenario. The aforementioned Boerelegioen group, and similar militia-like organizations, are stockpiling resources not necessarily to perpetrate genocide, but under the belief that they will need to defend against one. This creates a powder keg situation: if such groups ever misinterpret events as the start of a “genocide” against them, they could launch pre-emptive violence. It is worth noting that a South African court in 2023 struck down a bequest intended to fund the Boerelegioen, precisely because the group’s aims (promoting racial separation and armed defense) were deemed against public policy. The court’s action suggests that authorities are aware of the dangers of these fringe preparations and are trying to stymie them.

On the other side, one might ask if xenophobic groups are gearing up for more systematic violence. So far, attacks on foreigners, while organized at the community level, appear opportunistic – involving crude weapons (sticks, petrol for arson) rather than stockpiled firearms or military-grade logistics. However, the frequency and spread of these incidents could be seen as a slow-motion “preparation” for wider pogroms. Xenowatch data recorded 565 xenophobic incidents and over 15,000 displaced people from 2014–2021. The persistent nature of these attacks, often tolerated by local officials, might embolden perpetrators and normalize violence, arguably laying social groundwork for more intense future atrocities if triggered by a crisis.

Crucially, there is no indication of the South African government planning any genocidal act – a key difference from classic cases of the preparation stage. In fact, as of early 2025, the country’s Minister of Agriculture is a white individual, and government policy explicitly rejects racial violence. An objective analysis by the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum’s Early Warning Project consistently ranks South Africa relatively low on the statistical risk of mass killing onset (especially compared to conflict-ridden states), reinforcing that no active genocide preparation is detected in official channels.

In conclusion, the preparation stage is not overtly observed in South Africa at this time – no one is openly drawing up “kill lists” or building extermination camps. However, the volatile mix of armed extremist factions, hate-filled rhetoric, and recurring mob violence means that the situation could rapidly deteriorate if a catalyst (for instance, a contentious election or economic collapse) occurs. South Africa is better described as at the polarization stage with a risk of sliding into later stages, rather than actively in the preparation stage now. The focus should be on de-escalating polarization to prevent any actors from moving into preparation for mass violence.

Persecution

Persecution is the stage where victims are identified and subjected to campaigns of violence, violations of rights, and forced displacement – essentially, they are “punished” for who they are. Unfortunately, South Africa has clear evidence of persecution against certain groups in recent years. This is most visible in the violent attacks and systemic harassment of foreign nationals, predominantly immigrants and refugees from elsewhere in Africa. These acts go beyond discrimination; they involve direct harm, often fatal. For example, in periodic waves of xenophobic pogroms (notably in 2008, 2015, 2019, and 2022), mobs have hunted down migrant workers and refugees in townships and city centers. In the infamous May 2008 riots, over 60 people were killed and at least 100,000 displaced as armed locals expelled foreigners from communities. More recently, in September 2019, a spate of anti-foreigner riots in Gauteng province left 12 people dead (including 2 immigrants) and forced over 750 foreigners to seek shelter in police stations for safety. Shops and homes owned by Nigerians, Somalis, Ethiopians, and other nationals were looted and torched. These are coordinated acts of persecution: victims are targeted explicitly for being “outsiders,” irrespective of any individual wrongdoing. South African officials have acknowledged this pattern; the government’s Justice Cluster reported on the 2019 violence and arrested dozens of people, though prosecutions have been rare.

Persecution of foreigners continues at a lower intensity in between large flare-ups. Human Rights Watch notes that even in 2024, when major violence ebbed, there were still 59 reported incidents of xenophobic discrimination and nearly 3,000 people displaced that year due to targeted harassment. Migrant communities live in fear of sporadic attacks, and many have been driven out of informal settlements or deprived of livelihoods. The African Centre for Migration & Society’s Xenowatch tracker documented 218 deaths and over 15,000 displacements from xenophobic violence between 2014 and 2021 – a toll that qualifies as severe persecution even if it is episodic rather than continuous. The persecution extends to routine policing: as mentioned, refugees and asylum seekers face arbitrary detention, beatings, and deportation without cause, simply because they are foreign. UN experts decried that “perpetrators enjoy widespread impunity for xenophobic rhetoric and violence”, underscoring how the failure to punish attackers perpetuates the persecution.

There are also claims of persecution against white farmers in rural areas, which have gained international attention. While white farmers have been victims of violent crime, including brutal farm murders, the question is whether this amounts to a campaign of persecution. Far-right groups and some foreign commentators have labeled these crimes “white genocide,” but courts and researchers in South Africa have found no evidence of an organized plot to target whites based on race. The numbers bear this out: farm killings are only a tiny fraction of overall homicides (0.2% of murders in 2024) and many victims are actually black farm workers, not exclusively white owners. Investigations show motives like robbery are more common than racial hatred in farm attacks. Thus, while white farmers do face high rates of violent crime (with dozens killed each year), this is not officially sanctioned or encouraged by propaganda in the way xenophobic attacks on immigrants are. It is arguably a serious criminal issue and a human rights concern – white farmers (and farmworkers of all races) deserve protection – but it does not equate to a state or societal persecution campaign akin to classic genocide stages. That said, the psychological impact on the Afrikaner farming community is profound; many feel terrorized and some have emigrated or armed themselves heavily, fearing they are being hunted. The government’s response has been to create rural safety plans and deny any racial motive, which leaves the farmers feeling unheard. Genocide Watch includes white farmers alongside immigrant Africans as groups at risk in South Africa’s polarization stage, acknowledging that this community perceives itself as persecuted and could indeed become a target if extremist rhetoric (like “Kill the Boer”) were ever acted upon.

Beyond race and nationality, persecution in South Africa can also be seen in other spheres: political affiliation has turned deadly in some provinces (for instance, intra-ANC rivalries in KwaZulu-Natal have led to assassination of dozens of politicians – a form of persecuting opponents, though not on an identity basis). Additionally, there have been cases of community-level ethnic tension – for example, during the July 2021 civil unrest, in the town of Phoenix, groups of predominantly Indian residents, fearing looters, formed armed vigilante units and ended up killing over 30 black Africans who they suspected as “outsiders” in their suburb. This incident had an ethnic persecution character (Indians targeting Zulu/African people) and caused national outrage and soul-searching about race relations. The Phoenix killings underscored that mistrust between different ethnic communities can rapidly escalate to violence and collective punishment, fitting the persecution paradigm.

In conclusion, persecution is already happening in South Africa on a notable scale – particularly against foreign nationals, who have been killed, beaten, and burned out of their homes and businesses simply for being foreigners. Some minority groups like white farmers feel under siege from violent crime and incendiary rhetoric, although evidence of an organized racial purge is lacking. The ongoing persecution stage is a dire warning: it indicates that if underlying issues are not addressed, the situation could deteriorate further, endangering more lives.

Local community members in Johannesburg carry a sign telling “Foreigners must go back home,” reflecting the hostile climate that has led to violent persecution of African migrants. Such public displays of xenophobia illustrate how openly some groups are targeted and scapegoated.

Extermination

Extermination – the mass killing legally defined as genocide – is the stage where the perpetrators attempt to physically destroy the target group. This stage is not occurring in South Africa at present. Despite the serious violence and hate outlined above, there is no campaign of mass murder with the intent to annihilate an entire ethnic, racial, or religious group. Government forces are not rounding up people for slaughter, nor are death squads roaming with genocidal intent.

It is important to clarify this, given the alarmist narratives that sometimes circulate internationally. For instance, former US President Donald Trump and others have suggested that a “large-scale killing” or even genocide of white farmers is happening in South Africa. This claim does not hold up against facts. According to a 2024 fact-check drawing on official crime statistics, white farmers’ murders constitute a “tiny fraction” – around 0.2% – of South Africa’s total homicides. In a nine-month period of 2024, only 36 out of nearly 19,700 murders in the country occurred on farms (and only 7 of those victims were actually farmers, the rest being farm workers). While any murder is too many, these figures show that there is no genocidal scale killing of white farmers – the notion of a systematic extermination of that group is “clearly imagined”, as a South African court put it. Moreover, genocide by definition requires intent to destroy a group in whole or part. South African authorities, including many black leaders, have explicitly disavowed any intent to harm the white minority (in fact, the inclusion of white politicians in the 2024 coalition government underscores a will to integrate, not eliminate). The United Nations definition of genocide is not met by the current situation in South Africa, and credible watchdogs do not contend that an extermination of any group is underway.

The violence against foreign nationals, while grave, also has not reached anything near the level of extermination or genocidal massacre. These tend to be sporadic mob attacks killing a dozen people here or there, not a sustained attempt to wipe out all migrants. There is no indication that those attacks aim to completely eradicate foreigners; rather, they are meant to terrorize and drive them away (which is persecution and ethnic cleansing in character, but not full “extermination”). South Africa’s immigrant population remains significant, and the vast majority have not been physically harmed – again, not to downplay the very real murders that have occurred, but to distinguish them from genocide.

That said, the risk of moving into an extermination phase cannot be entirely discounted for the future. Genocide Watch has South Africa on alert precisely because the upstream stages are present, and history shows that if conditions worsen (e.g. economic collapse or extremist political victory), a deliberate campaign of mass killing could conceivably be incited. For example, if an extremist government came to power and decided to blame foreigners for national woes, they might move to mass violence. Or if racial tensions exploded in a civil conflict, certain areas could see attempts at ethnic cleansing. These are contingencies – not realities today. As of now, South Africa does not have extermination or genocide occurring, and it ranks relatively low in global genocide risk assessments. Both local courts and international observers (like the Lemkin Institute and Genocide Watch) agree that the notion of an ongoing genocide in South Africa is a myth, albeit a myth that extremist propagandists cynically invoke.

In summary, Extermination (Stage 9) is **not evident in South Africa at present. The violence that exists, while serious, remains limited in scope and lacks the characteristic intent to eliminate an entire group that defines genocide. The challenge is to prevent the current violence from escalating to that catastrophic level.

Denial

Denial is the final stage, typically occurring after a genocide, when perpetrators try to cover up or justify their crimes and blame the victims. Since South Africa has not experienced a genocide in the modern era (apartheid was a system of oppression but not an outright genocide by the UN definition), we do not see “denial” in the classic post-genocidal sense. There are no mass graves to hide or genocide to negate. However, aspects of denial can still be relevant in the ongoing context, insofar as officials or society downplay the warning signs and the targeted violence that is happening.

One form of quasi-denial is the tendency of some leaders to refuse to acknowledge xenophobic violence for what it is. For example, during a series of anti-foreigner protests in 2022 at a hospital (where locals demanded that foreign patients be turned away), President Ramaphosa insisted that South Africans are “not xenophobic” and characterized the nation as “welcoming”. While likely meant to protect the country’s image and encourage good values, such statements come off as denial to those experiencing the violence. Similarly, after the deadly riots of 2019, some government ministers emphasized generic “criminality” rather than naming xenophobia as the driver, which human rights observers criticized as evasive. The UN Special Rapporteurs explicitly warned that South African authorities were failing to “hold perpetrators accountable” for xenophobic attacks and that this impunity, coupled with official scapegoating of migrants, was extremely dangerous. This failure to fully acknowledge and address the problem can be seen as a form of denial – not denial of genocide per se, but denial of the gravity and prejudice underlying these crimes.

Another facet is the denial or dismissal of potential genocide risks. When confronted with concerns (for instance by Genocide Watch or foreign governments) about the hate speech against white farmers, South African officials often respond that there is no such thing as “white genocide” happening – which is true, as we have noted, but sometimes this response is accompanied by a dismissive attitude toward white farmers’ legitimate fears. Balancing truth and empathy is tricky: yes, the claim of an ongoing white genocide is false, but denying the community’s sense of vulnerability outright can feed their insecurity and distrust in authorities. Encouragingly, South Africa’s courts have taken a strong stance against false genocide narratives: the case that blocked funding to the Boerelegioen also served to judicially declare that the idea of a current white genocide was “not real”. This was effectively an official repudiation of a denial-like myth (since white nationalist groups pushing that myth are, in a sense, denying the reality that no genocide is happening and instead constructing a false victimhood narrative).

It’s also worth noting that perpetrators of xenophobic violence often deny or rationalize their actions. Interviewers have found that local attackers frequently claim “foreigners are criminals” or “they took our jobs” as a way to justify their brutality, essentially blaming the very victims of their attacks for the situation. This parallels the denial stage where blame is shifted to victims (e.g., “they brought it on themselves”). Similarly, extremist rhetoric from the EFF denies any intent to incite actual violence – for example, EFF leaders say singing “Kill the Boer” is just a historical protest song or metaphor, not a literal directive. They publicly maintain that they do not seek to exterminate whites, even as they continue provocative language. Such denials muddy the waters: outsiders see clear incitement, while the inciters insist on an alternate interpretation, thus avoiding accountability.

In conclusion, denial in its strictest sense (hiding a genocide) is not applicable to South Africa in 2025, as no genocide has occurred. However, denial in a broader sense – the refusal to fully confront and label the existing targeted violence and hate – is present. Whether it’s officials understating xenophobia, or perpetrators rationalizing their attacks, this tendency hinders effective prevention. Acknowledging reality is a prerequisite for action, so overcoming denial-like attitudes is important to ensure the early warnings (classification through persecution) are heeded and never allowed to progress to extermination.

Conclusion and Risk Evaluation

South Africa’s current situation exhibits many early and intermediate stages of the genocidal process, though it has not reached the ultimate stages of genocide (extermination) and post-genocide denial. The environment is fraught with group tensions – racial, ethnic, and national – and there are clear patterns of hate speech, propaganda, and episodic violence against specific communities. These are warning signs that merit serious attention. At the same time, there are resilience factors: a strong constitutional framework, active civil society, an independent judiciary, and public rejection (in many quarters) of extreme racism, all of which act as bulwarks against a slide into genocide.

Each of the ten stages can be assessed in terms of its presence and the associated risk level in South Africa today. The table below summarizes which stages are observable and provides brief supporting evidence for each:

| Genocide Stage | Presence in South Africa | Evidence and Examples |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Classification | Yes (High) – Society is markedly classified along racial and national lines. | Politicians and media often invoke an “us vs. them” narrative, e.g. citizens vs. foreigners. Election campaigns scapegoated foreign nationals as a group. Racial identification remains salient (black majority vs. white minority), contributing to “highly polarized” social relations. |

| 2. Symbolization | Yes (Moderate) – No official badges, but plenty of derogatory labels and symbols in use. | Immigrants are branded with slurs like “amakwerekwere” and even called “cockroaches” in hate speech. Extremist rhetoric uses terms like “house negro” or “white monopoly capital” to negatively mark groups. Such language serves to stigmatize target communities. |

| 3. Discrimination | Yes (High) – Institutional and social discrimination against certain groups is evident. | Migrants face institutionalized xenophobia: unlawful arrests, exclusion from jobs, and mob “inspections” of their status. Policy examples include crackdowns on foreign-owned shops and proposals to bar non-citizens from certain work. Historical redress laws (BEE/affirmative action) also create perceived discrimination (though intended to reduce inequality). |

| 4. Dehumanization | Yes (High) – Open dehumanizing hate speech is present, fueling violence. | Xenophobic actors compare foreigners to vermin and call for them to be “killed” like pests. One mob burned a man alive in 2022, showing how far this rhetoric has desensitized attackers. On the racial front, an EFF leader’s statement “not calling for slaughter… at least for now” regarding whites dehumanizes that group as a pending enemy. Such language strips away the humanity of targets, making violence more acceptable. |

| 5. Organization | Yes (Moderate) – Hate is manifest in organized groups and movements, though not state-led. | Vigilante groups like Operation Dudula systematically mobilize communities to target migrants (coordinating protests, incursions into migrant areas). Some political parties leverage these networks as part of their platform. Meanwhile, extremist militias on the fringe (e.g. white separatist groups) have tried to organize for a feared conflict. The state is not organizing genocide, but non-state groups are organizing persecution. |

| 6. Polarization | Yes (Very High) – Society is deeply polarized, and extremist propaganda dominates the discourse. | Genocide Watch rates South Africa at Stage 6 (Polarization) as of 2025. Hate groups and demagogues intensify divisions: anti-immigrant propaganda (“Put South Africans First”) and racially charged narratives (from EFF on one side, white nationalists on the other) split communities. Moderating voices are often drowned out or attacked, as seen when cooperation between races in politics was met with slurs (“slave master”, etc.). This polarization increases the risk of violence. |

| 7. Preparation | Not in effect (Low) – No evidence of an active plan or preparation for genocide by authorities. | There are no death lists or arming for mass killing by the government. Security forces are not preparing camps or the like. However, elements of society are bracing for conflict (e.g. some militias hoarding weapons defensively). The absence of formal preparation is a good sign, but vigilance is needed to ensure extremist talk doesn’t evolve into concrete plans. |

| 8. Persecution | Yes (High) – Targeted violence and rights abuses against identified groups are ongoing. | Foreign nationals have been beaten, burned, and killed; their shops looted and homes torched in repeated waves of attacks. Thousands of refugees/immigrants have been displaced or live in fear. Impunity for these crimes is common. Politically, dozens of people (mostly black) have been killed in intra-party or ethnic clashes, indicating persecution of perceived “enemies” in some local contexts. White farmers experience high rates of attacks, though evidence suggests criminal motives in most cases. In sum, violent persecution of certain groups is a reality in South Africa’s landscape. |

| 9. Extermination | No (None) – There is no genocide or mass extermination campaign currently in South Africa. | Killings are limited and localized, not mass or state-sponsored. For instance, farm murder rates are a tiny fraction (<0.3%) of overall homicides, and no group is being systematically destroyed. The government includes all races and officially condemns group-directed violence. While the situation is volatile, it has not crossed into genocide, according to all credible monitors. |

| 10. Denial | N/A (or Present in part) – No genocide has occurred, so classic denial (hiding massacres) is not applicable; however, some denial-like attitudes hinder addressing the violence. | Officials sometimes downplay xenophobia, insisting “South Africans are not xenophobic” even amid attacks. Extremists deny inciting hate (e.g., claiming chants are metaphorical) or propagate false narratives (the myth of “white genocide”). These behaviors echo the denial stage’s mindset – blaming victims or refuting the truth – and impede conflict resolution. |

Overall assessment: South Africa is not experiencing genocide, but it sits at a dangerous crossroads with several pre-genocidal stages active. Classification, discrimination, and dehumanization of groups (particularly foreign African nationals, and to a lesser extent racial minorities) are evident and have led to periodic bursts of persecution in the form of violent attacks. Hate speech and organized vigilante actions have created a level of polarization that Genocide Watch flags as serious. The later stages (preparation, extermination) have not materialized, which is critical – it means there is still time to prevent the worst outcomes. However, the presence of multiple early stages suggests that South Africa carries a non-negligible risk of mass atrocities if these trends are not reversed.

The risk level for each stage can be summarized as follows: South Africa has a high risk in stages 1–6 and 8 (warning stages and persecution), given that we see active division, hate propaganda, and recurring violence. The country currently has a low risk in stage 7 (preparation) – no concrete genocidal plots detected – and effectively zero occurrence of stage 9 (extermination), which is the good news. Stage 10 (denial) is partially relevant insofar as it manifests as denial of issues, not denial of genocide.

Recommended actions (implicitly following from this assessment) would be intensifying efforts to combat hate speech, holding perpetrators of xenophobic and racial violence accountable, and promoting dialogue to depolarize society. Indeed, Genocide Watch’s recommendations urge South African leadership to reform policing, ensure justice for attacks on both immigrants and farmers, and denounce incendiary groups like the EFF to cut off the fuel of polarization. Strengthening the rule of law and social cohesion now can halt progression to the later genocidal stages. South Africa’s vibrant civil society and independent judiciary are assets in this struggle, as shown by court decisions upholding human rights and debunking false genocide claims.

In conclusion, South Africa manifests several early stages of the genocide process, signaling significant societal stress and conflict. These conditions demand proactive measures but do not equate to an inevitable genocide. The country’s fate will depend on acknowledging the very real warning signs – rampant xenophobia, racial animosity, and violent persecution – and decisively addressing them. By doing so, South Africa can reduce the risk that these warning stages escalate, and instead move toward healing the divisions that extremists have worked to widen. The current evidence suggests a cautious vigilance: the ten stages of genocide serve as a checklist of dangers, many of which South Africa must urgently confront to ensure it never reaches the final, tragic stages of that continuum.

Sources: Recent reports and analyses have informed this assessment, including Genocide Watch alerts, United Nations experts’ statements, Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International findings, reputable news agencies (AP, BBC, France24, ABC) for on-the-ground events, and fact-checking organizations that clarified the extent of violence. Each citation in the text corresponds to a source backing the factual claims made. The consensus of these sources is that South Africa is at risk but not doomed – showing several precursors of genocide that call for immediate attention, yet also having the institutions and public will that, if mobilized, can prevent the situation from ever reaching the point of no return.